The design process is an organized method to gather the thousands of decisions needed to design a building, ranging from the big picture vision and architectural image to excruciating details about every system and every surface in every room. Despite having a well-established process honed over centuries, too many projects are completed late, over budget, and sometimes have not fulfilled the original goals or vision. Even a top-notch team steeped in all of the latest digital tools and Lean techniques can still run aground if they don’t understand the decision-making process in design and construction.

This 3-part article series will explore how people make decisions, what they need to make decisions, ten techniques project teams can use today to reduce costly changes by helping others make better-informed decisions, and how to protect their decisions.

Most of the tips in this series can be used by anyone on the team: owners, architects, engineers, and contractors.

You will discover:

- The psychology of decisions, decision-making styles to support the design process, and what do we need to make decisions?

- Ten techniques to foster informed decision-making

- What owners can uniquely do

This article will cover item 1.

Are your projects sometimes troubled by indecision and/or changing decisions?

Do the so-called “decision-makers” delay needed decisions or make last-minute changes costing everyone time and money?

Early in my career as a young architect, I was fortunate to join a large architecture/engineering firm where I specialized in helping clients make pre-design decisions for a wide range of projects and building types. In other words, I ran meetings with clients for a living. As time went on, I advanced into project delivery as a project manager, director and architectural principal. Decades of client-focused experience from pre-design through construction, coupled with an interest in learning about decision-making outside of design and construction, were invaluable. They provided a deep understanding of how people make decisions and what information they needed to make decisions they can stick to (or live with) throughout the design and construction process.

Having presented on this topic dozens of times to audiences around the country, I have observed that experienced practitioners seem to appreciate this line of thinking more than younger folks. Perhaps this is because early in our careers we are busy learning our craft, then later learning to manage a team and projects. It is not until we have gained experience running a wide range of projects that we can see that some projects were more successful than others, not because of anything the team did directly, but because of the decision-making process used.

So what can architects, engineers, designers, builders, and owners do during a project to help get decisions that stick?

To avoid delays caused by changes or indecision, and instead obtain timely decisions that stick, requires greater attention to facilitating informed decisions. Design and construction teams who simply ask an owner for a decision--without providing all the information and implications of that decision--risk having that decision changed later. And what will be the impact on the delivery of the project?

- The psychology of decisions

"The worst waste is the stagnation of decision making processes in top leaders." Jun Nakamuro, Certified Coach in Taiichi Ohno's Lean and Kaizen

It helps to understand how humans make decisions. While multiple people will think differently about the same subject, there are broad patterns that can help us understand and plan for decision-making. These lessons apply to all types of decisions, not just in design and construction, but in all aspects of life--whether simple decisions like choosing your lunch, to greater commitments such as deciding on a career or a spouse.

Let’s explore some decision maker archetypes and decision making styles.

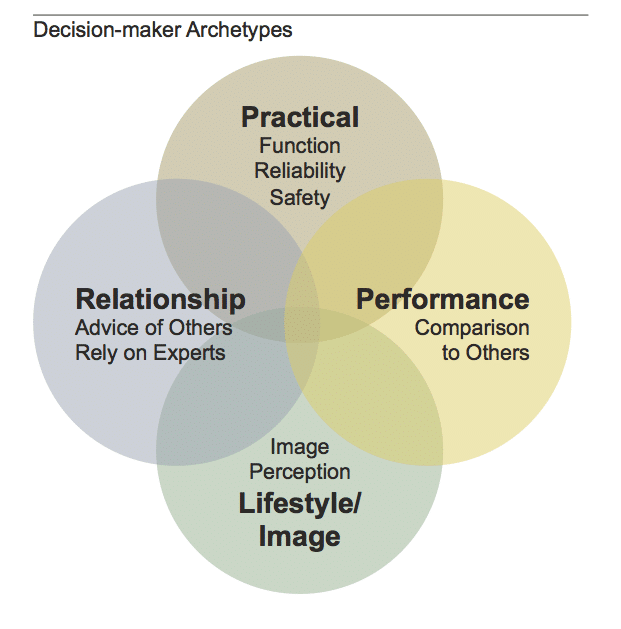

Most decision makers fall into one of the following four archetypes when they make a decision, depending on their goals and priorities at the time they are buying.

- Practical

- Performance

- Lifestyle

- Relationship

What is influencing your decision-making process?

Imagine you are buying a car. Some people make decisions for mostly practical reasons, such as reliability, fuel efficiency, safety features and number of cup holders. Others may be at a point in their life where they are looking for high performance, so a car’s 0-60 mph time and the rumble of the exhaust may be most important. Still others are looking for a lifestyle car. They can picture themselves with the top down, wind in their hair, music booming, etc. And still others don’t weigh any of the above; they are influenced by a relationship. Perhaps a friend recommended that they’d like a certain vehicle, or they trust the recommendations of the salesperson.

Now imagine you are selling cars. Can you see how helpful it would be to know what information is important to buyers and how they make decisions? If you start your pitch with a car’s safety rating and crashworthiness, that information might not be among the criteria that a specific buyer needs to make a decision.

So to help someone make a decision, look for clues showing what types of information that decision maker values.

How do people make decisions?

Then, there are the decision making styles. Some people and organizations are autocratic (where the top person makes the decisions), some are more consultative (they may ask for a consultant or expert to weigh in, but the person will still make the final decision), and some involve the team to find a solution acceptable to all. Which strategy is most productive depends on the situation.

Organizations, like individuals, have decision-making styles as well. Some building owners, especially those who design and build often, may rely on their proven standards and a small number of decision-makers. Other organizations prefer a more inclusive process. This typically takes longer but it may lead to facilities that better respond to the unique needs of the users. (It can sometimes lead to more customized, idiosyncratic, and less flexible solutions.) The key is that the design and construction process needs to adapt to the way the customer’s organization makes decisions.

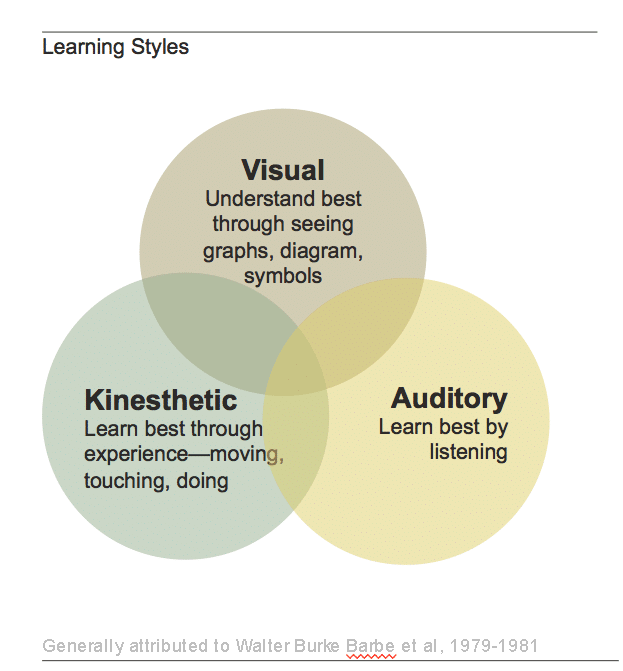

The next thing to consider are the different learning styles:

- Visual

- Auditory

- Kinesthetic

Most people have one or two dominant modalities by which they learn best. A related model is VARK: visual, aural, read/write, kinesthetic. Take the VARK test to find out about your learning style.

Similarly, the Boy Scouts of America has found that the most effective way to teach anything--from knot-tying to leadership skills--is with the EDGE Method, which combines all learning styles:

- Explain

- Demonstrate

- Guide

- Enable

I am sure it is not a coincidence that explain is auditory, demonstrate is visual, and guide is kinesthetic, covering all of the styles for most effective learning. Finally, enable means to start doing and ideally teaching someone else.

What does this have to do with how we make decisions in lean construction projects?

How people learn is important because if you want to get someone to make a decision, you normally introduce the decision to be made, explain the background and any analyses that have been conducted, and very often present options to be considered.

The decision maker has to understand and learn what you already know. You might have been researching, learning about this topic and analyzing it for weeks so that you are capable of presenting it to your client or boss in a matter of minutes. Which means your audience has to learn everything you've done over weeks in a very short time to make an informed decision. So understanding how people learn is an important part of how you can help them make an informed decision.

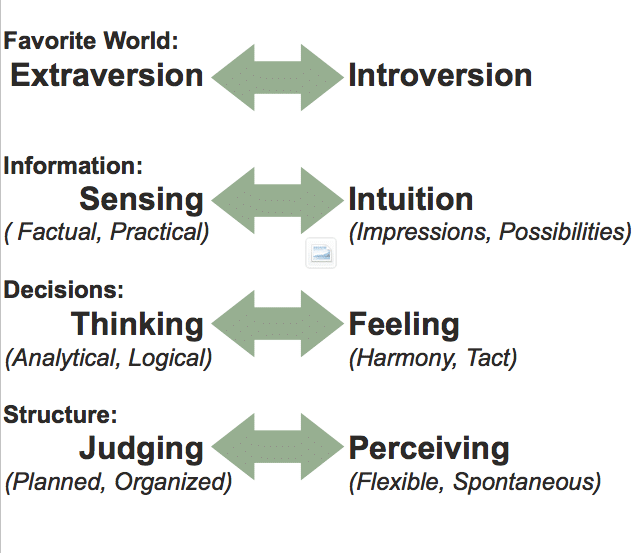

Lastly, there are the Myers Briggs personality types and how different personality types tend to make decisions. Myers Briggs recognizes that how we each make decisions is an important dimension of our personalities. In their vocabulary, some people make decisions using “Thinking (analytical, logical)” while others use “Feeling (Harmony, Tact).” This is a range or spectrum, so while some people may be at each extreme, others are near the middle or lean one way or the other depending on the decision. If you are helping someone make a decision or asking them to make a decision, be acutely aware that the way you make decisions is not necessarily the way the people you're presenting to make decisions. This is challenging for many people, perhaps because they assume everyone processes information the same way they do.

The more you can understand and embrace the diversity of the people you interact with, the better you will communicate and the better the results will be.

2. What do we need to make a decision?

To communicate effectively, we need to speak in a language the other person understands. If I speak only English to someone who speaks little to no English, then I am not being an effective communicator. This certainly applies when asking someone for a decision. Make sure that you present and explain all the information people need to make a decision in a way that is easy for them to comprehend,which may not be the way that is easiest for you to express!

For example, if I am asking someone to choose between two shades of blue, it would be easiest for me to just say, “one is darker and one is lighter.” But if you were trying to choose a blue color, is a vague verbal description enough? In most cases, it is not. You probably want to look at the two colors, ideally side-by-side to compare them. Or a decision-maker may want to look at the colors in context. For example, “This blue shirt with those jeans or that blue shirt?”

A verbal description, in this case, would not adequately convey the information a decision-maker needs. Or, what’s worse,they may choose based on the description, but the decision will change once they see photographs or the actual colors or see them installed.

Projects can run into problems when an architect shows a client a floor plan and asks for approval (a type of decision). If the client is not fluent in reading floor plans, they will do their best to follow along and make a decision with the limited information they understand. But later, once they more fully understand the space in question, for example through a scale model or a full-size mock-up or once the building’s walls are built, then they are likely to request changes.

The previous decision didn’t “stick” because the way the question was originally communicated did not support the client in making an informed decision.

So how do we make decisions?

People generally make decisions by internally asking themselves and trying to understand:

- What is the question being asked?

What are the goals we are trying to achieve and/or what decision criteria am I supposed to evaluate against?

- What options are available?

Yes/no? Rate from 0-10? Options A, B, C?

- Which of the available options best answers the question or meets the criteria?

And if none of them meet the goals or minimum threshold, are there other options that do? If not, perhaps we should revise the selection criteria.

To evaluate which option is best, we mentally weigh pros versus cons, costs versus benefits, risks versus rewards.

For most decisions, people generally look first at the following four criteria. The order in which these four are evaluated will vary with the situation and the decision-maker’s personality. Often, people first eliminate options that do not meet the minimum criteria, then they mentally rank the remaining options against each other.

A1. Function - Does each option meet the fundamental criteria already established, such as the capacity or minimum numbers? If not, those options get weeded out quickly.

A2. Cost - Is each option within the established budget criteria? Is one option better value than the others, meaning lower cost for perceived benefits?

A3. Schedule - Some options can be eliminated if the schedule or availability is beyond the goal. And similar to budget, is one option faster for the same functions? Time-to-market is very important in construction projects.

A4. Image/Form - When asked to make an aesthetic choice, say, about interior or exterior design options, this consideration is obvious. But I have found that image is an important consideration far beyond that. Most of us do consider how a purchase or decision reflects on who we are or who we aspire to be. This is true not only in your clothing, hairstyle, jewelry, eyewear and vehicle you drive, but in everyday decisions such as “your” coffee cup or the pen you use.

How we mentally process information to make a decision

Beginning in the late 1960s, the Problem Seeking approach to architectural programming identified function, form, economy, and time as primary considerations, or categories of considerations, to be used in programming and designing buildings. I have found these are just as valuable today because they reflect the way we mentally process information to make an informed decision.

Sometimes, when evaluating options against the above four considerations, one winner rises to the top and a decision is clear. Other times, after the above evaluations, more than one option is still in the running. To make an informed decision, I find that people then consider some combination of the following to identify the best option and make a well-informed decision:

B1. Flexibility - Does one option provide greater (or lesser) flexibility than the others? If our projections are wrong and we need more or less space, or if we have more or fewer people, for example, does one alternative provide more or better options?

B2. Upside/Downside - Are there any additional benefits (upside or downside) to one option that might tip the scales?

B3. Other Value Judgements - How do the options stack up on “softer” measures such as fairness, ethics, morality, sustainability? Many organizations make decisions looking at the “triple bottom line,” considering not only financial but also social and environmental impacts. After the events of 2020, more organizations are intentionally considering justice, equity, diversity and inclusion in their decisions than ever before.

B4. Relationships/Politics - Are any options politically more viable than others, meaning do we believe some options may encounter resistance or outside pressure, and how much do we want that to influence the decision? Are there other factors the decision-makers may be using, aka “hidden agendas,” such as the stereotypical “brother-in-law deal”? For a facility project, does one option make us a better neighbor or will it be better-received by the community?

Depending on the project or the decision, some of these (such as sustainability or being a good neighbor) may be intentional goals or primary decision criteria.

While there are many ways to evaluate and weigh these competing criteria and considerations, readers may be interested in learning more about the approach advocated by the Lean Construction Institute, called Choosing By Advantages, or CBA.

Decisions are fragile

Through decades of studying how people make decisions, and helping them make better-informed decisions, I have come to realize that decisions are fragile. Since many decisions are based on facts and projections, if any of those inputs change, it will often change the output, meaning the decision.

There are at least two strategies to reduce the chances of later inputs unravelling a decision:

- Scenario Planning and Sensitivity Analysis - Any time there are clearly defined formulaic solutions to inputs, then we really don’t need a decision. (“Follow our company standard” or “Tuesdays are always taco night.”) Therefore, most of the times we need a decision, there is not a hard rule and/or we are working with assumptions and forecasts that require buy-in. Decision-makers need to understand how variability of the inputs can change the outputs or forecasts they are relying on to make a decision. Based on the information provided, they will make a decision. But if they later find out that the forecast varied more than they expected, that may change their decision. The way the information is presented can lead to a decision that doesn’t stick. Therefore, it is better to be up-front about the range of inputs and the effect on the forecast. For example, it is better to say, “this cost estimate is $X +/- 10%” and explain what influences the 10% than to only provide the $X. That way, if the inputs do vary within the range you forecast, then the decision is less likely to be overturned later. Sensitivity analysis can be applied to things like how closely tied the number of people or customers is to the square feet needed. In scheduling, it is helpful for the team to not only understand the critical path, but things like, “If we get permit approval sooner than we think, then which activities are on the critical path?” A greater understanding of how things might change in the future allows us to better position ourselves today in case an alternative future plays out.

- If you want a decision to stick, you need to protect it. If the culture of decision-making allows anyone (even influential people) to undo a previously-made decision at any time, that’s a recipe for problems. To get decisions to stick, there must be an agreement on when certain decisions need to be made, who needs to be involved in making that decision, and what information they need to make an informed decision. Once there is agreement from all participants on what the decision process will be and who will be included, then decisions are more likely to stick. This does require that the top decision-makers (typically the Owner on construction projects) commits to this. More on that in Part 3 of this article series.

Finally, here are 10 Fundamentals to make decisions that stick

- Communicate in Their Language

- Provide Info Needed for Informed Decisions

- Selection Matrix May Help

- Develop Decision Protocol w/Customer

- Find the Real Decision-makers

- Establish Levels of Authority

- Who Can Derail or Veto? - Explain the Process to Participants

and the gravity of timely decisions - Facilitate Decisions

- Does This Decision Need to be Made?

- Go to Gemba (where the work is done)

- Only Ask Questions You Want Answered

- Help Your Customer Answer Difficult Questions

Interested in learning more about the ten techniques that anyone on a project team can use to foster informed decision-making? Read part II of this series.

Book Tip:

From the LeanIPD blog

Sharing is Caring (Part 1)

Where Attention Goes, Energy Flows (Part 2)

Create a Space to Play (Part 3)

Kurt Neubek is a Principal, Firmwide Healthcare Practice Leader, and Lean Advocate with Page, a 650-person architecture/engineering/interiors/planning/consulting firm with nine offices across the US and abroad. He has over 30 years of experience and has programmed and planned tens of millions of square feet of space across the globe. Kurt is an award-winning speaker, having presented at more than 90 national and regional conferences. He is a Fellow in both the American Institute of Architects and the Health Facility Institute, a Certified Facility Manager, LEED Accredited, Evidence-based Design Accredited and Certified, and a Six Sigma Black Belt. He is also an instructor for the Lean Construction Institute and the Construction Owners Association of America.