In the first part of this series Getting Decisions that Stick, we looked at the psychology of decisions and what information people need to make informed decisions. This article describes ten techniques to help decision-makers make better-informed decisions in PreDesign, Design, and Construction. Such decisions are more likely to “stick,” reducing costly changes and rework while improving project flow and team morale.

- Find the real decision-makers

The first step to make better-informed decisions in Predesign and construction is to identify all of the decisions that will be needed and who gets to make each of those decisions. The answer will vary depending on the organization and often the scale of the project, but there may be a longer list of decisions and decision-makers than many people realize. For example, the overall schedule and budget constraints are usually set by a senior executive or executive committee. For site-related decisions, there may be a separate committee. The intended occupants (often called “users”) or surrogates typically get to provide forecasts and input and make decisions about how they will operate--as long as their ideas fit within the project scope, schedule, and budget. Many organizations have a facilities group that gets to establish project delivery, facility planning, workspace, furniture, equipment, signage, and similar standards. There is often a facility operations team who may be given authority to make maintenance-related decisions. The authorities having jurisdiction will often need to be consulted for certain decisions, clarifications, or rulings that only they can make.

Even though architects and engineers generally present options to the owner for decision, there are so many decisions to be made during the design process that owners count on their A/E team to make many of them. For example, at what level of detail does the owner want to review the specifications? Will they rely on or defer to the A/E or a specialized consultant for certain decisions? It is important to identify all of the players and what level of decision authority they will have?

- Who else, if they weigh in late, could possibly derail or undo a decision?

Once the list of decision-makers is identified (and which decisions they will be asked to make), in nearly all situations I have found that there are additional people who should also be included. These are people with the authority or influence to veto, revise, or override those decisions, often very late on a project. It could be a senior executive, a board or board member, an elected official, a neighborhood organization, or even the spouse of a key decision-maker. Get these people involved early! Ask them for their goals, concerns, constraints, and other thoughts. Since they have the ability to change the outcome at the worst possible time, it is far better to get their input early, at the best possible time.

If these people or groups are external to the organization, find a way to gather their input early and keep them apprised of the progress. If they are internal to the organization, it is ideal to have regular meetings with them or to have them participate in meetings they are concerned with. For example, on many projects where the organization wants to do things in a new, innovative way, it can be enormously beneficial to have the COO or senior person charged with driving the change to sit in on the early formative meetings with user groups or department representatives. Otherwise, those people will naturally tend to ask for what they know or what is familiar. Having a senior person helping them understand how the new vision will impact operations and the decisions being made today pays enormous dividends.

- Work with your customers to develop a Decision Protocol

To make better informed decisions in Predesign and construction, it is also important to discuss and agree on how various decisions will be made. What will be the protocol? The answer will vary with the organization and often with the project type and scale. As the number of people in the owner’s organization increases, there are not just “decision-makers,” there may be many more people who need to “weigh-in” or be “consulted” on a topic before someone else can make the decision. For example, even if there is a small group authorized to make most of the decisions, for certain decisions, this group may need to make recommendations to say, an Executive Steering Committee, who actually makes the decision. Do “user groups” simply get input without real decision authority, or are they the “customer” with decision authority over certain areas?

Consider the overall scope, including schedule, budget, building core, building systems, department/user areas, and equipment. The decision protocol for each of these may be different on the same project. To get decisions that stick, it is enormously beneficial to be sure there is agreement on what those protocols and approval paths will be from the beginning.

Image via Unsplash

4. Establish Levels of Authority

A common way to capture and communicate how decisions will be made is with a Responsibility Matrix. There are a number of acronyms used to describe these, such as RASIC. For each category of decisions, who is:

- Responsible? (Only one person or committee for each decision!)

- Approving?

- Supporting?

- Informed?

- Consulted?

Similar acronyms are RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) and LACTI (Lead, Approve or Accountable, Consulted, Tasked, Informed). This will help formalize not only who will make the decision, but which other people should be involved. It may also help you identify any foreseeable exceptions to those rules.

- Explain the process to everyone involved

If you are designing a project where one person makes all of the decisions, a formal chart, diagram or matrix may not be necessary. But the more participants, the greater the benefit of documenting in one place how decisions will get made, as long as the process is shared with everyone who needs to understand it. The sooner in a project you can identify all of the decisions (or at least categories of decisions), the process or protocol for making them, and get those things documented and shared with the entire project team, the more likely decisions can be made in an organized and timely manner.

Be sure to share the decision process openly and visibly. Many project teams organize all of the above steps from the very beginning in order to share the process in a Project Kick-off Meeting. Using slides, posting it on the wall in a project room, and sharing via email or team site are all effective ways to be sure the process is being communicated genuinely.

What may not be obvious about sharing this process with everyone is the benefit to the people who do not get to make decisions. I have found that, almost universally, people who participate in design and construction projects are very reasonable and they know they may not get everything they ask for, if it was not budgeted, or if they do not have a solid business case or payback analysis to support it. But people do universally want to know that their input, concerns and opinions will be heard and that their perspective will be considered--even if in the end they don’t get what they asked for. I have heard many testimonials and feedback from participants over the years making this point. The impact that an open decision-making process can have on a project team’s morale should not be underestimated.

- Don't ask for decisions, facilitate them

This three-part series about how to make better informed decisions in Predesign and construction is based on a presentation I have given to thousands of people at a variety of conferences around the country. In the live event, I ask people to make a series of simple decisions, and their decision is displayed on the big screen in real time. We start by showing three options for lunch: a sandwich; burger, fries & shake; and a salad with salmon. We ask them to choose which they would prefer for lunch. They vote by texting with their phones and the results are immediately displayed on the big screen. Once that decision is made, I let them know the cost: The sandwich is free, the burger & fries will cost them $11, and the salmon salad will set them back $22. They then have an opportunity to change their decision. Many of them do. (Many more take the free sandwich.)

In the third round I explain the schedule: The sandwich is available immediately, the burger & fries will take 10 minutes, the salmon 25, and they only have 30 minutes for lunch. Does that change their decision? They vote again (and fewer people choose the salmon). Next we give them some nutritional information they didn’t have before: The reason the sandwich is free and available immediately is because it’s leftover from yesterday. The burger meal is 2,300 calories, and the salmon is the only heart-healthy option. They can change their decision if they’d like. (Sandwich takers normally drop to almost zero.) In the final round, I pass along some information about relationships and values. Will it influence their decision about a lunch choice? I tell them the sandwich is made by a local start-up, the burger by a large multinational conglomerate, and the salmon comes from a sustainable store that is owned by a friend of theirs. The audience gets to change their decision and the results are displayed on the big screen. (Often there is more support for the sandwich and significantly more votes for the salmon salad.)

I jokingly point out how fickle and indecisive the audience has been over such a simple decision as what to have for lunch! Why? Their decisions kept changing because of the way I presented the information they needed. I kept trickling in information that was important to some of them. In this case I did it intentionally, but we need to ask ourselves:

How often are we (unintentionally) doing that to the decision-makers on our projects? How much are we contributing to the indecision?

Too often we give decision-makers partial information about a situation, we ask them for a decision, and they dutifully and sincerely try to make the best decision they can given the information available at the time. But if they later find out the cost, schedule, or other implications, we can’t blame them for changing their minds. In fact, we may have caused them to change their minds.

To get decisions that stick, we need to provide decision-makers all the relevant information needed to make an informed decision. (See Part 1 for more on the categories of information people need to make decisions.) This requires more attention early in the project but will streamline the rest of the project and reduce wasteful revisions caused by changing decisions.

- Start with the bigger decisions

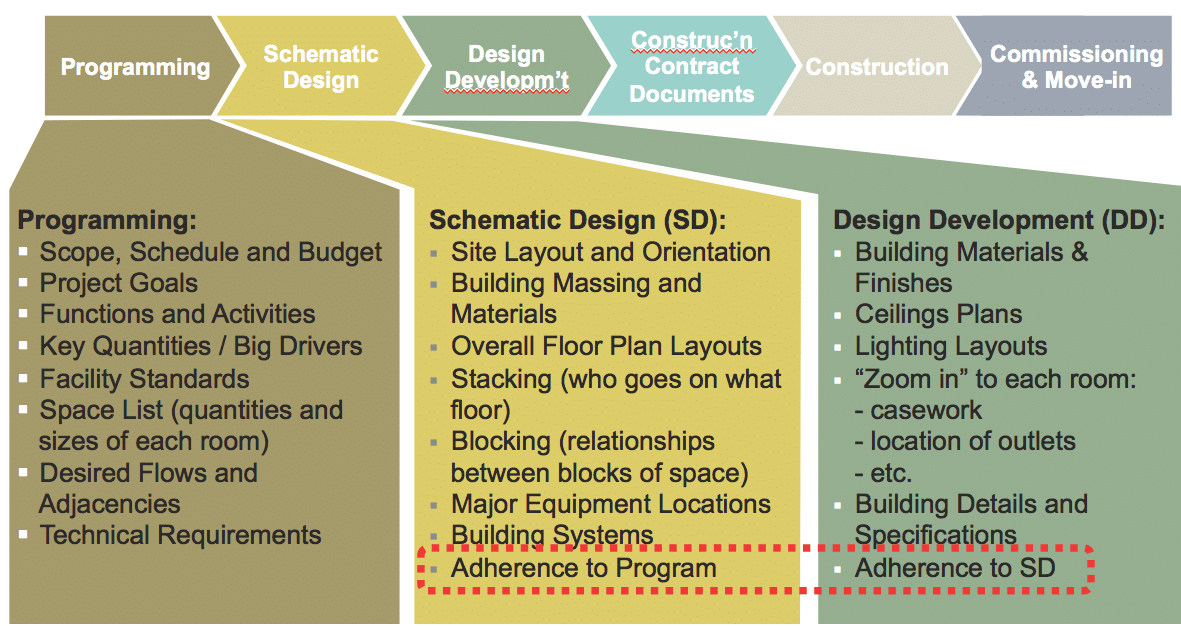

Make sure people understand the agreed-to decision-making process and which decisions have to be made at which stage. There are good reasons the design process begins with Strategic Planning then moves to Master Planning, PreDesign (Scoping/Programming), Schematic Design (SD), Design Development (DD), and Construction Documentation (CD). While some people believe that design is an iterative process, I disagree. Iteration is defined as repetition of a process. Isn’t it wasteful and unnecessary to intentionally repeat or rehash a topic more than once? Instead, if we provide decision-makers all the information they will need to make a decision that will stick, we can make each decision once, then move on to different decisions in each phase. Make programming decisions during programming (vision, goals, number of rooms, size of rooms, relationships and flows between rooms, etc.), Schematic Design decisions during SD, Design Development decisions during DD, etc. If we make it clear to everyone from the beginning that the activities, functions, capacities, and overall scope of the building will be decided during programming--including the quantities and sizes of rooms--then people will bring up their concerns and suggestions about those topics at that time. But if we don't make that clear, people are much more likely to raise such concerns during SD, DD, CDs, or once they get to walk around the building. The later in the process a valid concern is raised, the more disruptive it is to the whole project. Therefore, establish a process to get input from people at the time it is most beneficial to the project.

I have been involved in many very successful projects where the client and the team agree that once we make a decision, we will not go backwards and rehash it again. We don’t have the time or the money to do that. We can keep adding granularity and details, but as we move on, we will not undo the previous decisions. Once a team understands that this is a fundamental rule by which the team has agreed to operate, following this significantly helps a team make decisions that stick.

Illustration: Kurt Neubek

I found that a diagram like this design process overview, highlighting the decisions to be made at each phase, is a valuable tool. It helps the entire team understand and communicate the process. We have used it at the beginning of every user group meeting, and it helps to make decisions once, during the optimal phase.

- Is a decision necessary?

People often waste time searching for decisions they don't need at the stage they are at. Some decisions will only need to be made three years from now and the inputs will be different. So don’t waste your time on arguing about something you don’t need right now to proceed with the project.

How do you plan for the future, while accommodating a range of decisions? To learn how things actually work—not how people believe they should work—in the language of Lean, I always recommend “going to Gemba,” the place where the work is done. Lean practitioners recommend, “Never make a decision in a conference room.” Whatever the topic, talk to the people working in the area in question, observe how they work, and have a constructive dialog. Getting information first-hand helps people make decisions with greater confidence. Therefore, they are less likely to get new information that changes their minds later.

- Only ask questions you want answered

When meeting with or interviewing people, don’t ask a question that the person is not authorized to decide. Too often I have heard people ask the owner or the users questions like: How big should that duct be? The size of a duct needs to be calculated by an engineer, so it is inappropriate to ask for the answer. It is, however, perfectly reasonable to ask for the inputs needed to run the calculations that the users can reasonably be expected to know: things like the intended uses of a space, the amount of equipment, how they plan to operate it, are there certifications needed, and perhaps the applicable regulations.

I have also heard design professionals ask questions, such as: “What kind of computer would you like, or how many copiers should we plan?” While planning furniture and equipment, the team certainly needs to understand the equipment to accommodate, but be sure to ask the people authorized to make such decisions.

Don’t ask questions they can’t know. Far too often I have seen (and even used) programming questionnaires that ask questions such as: “What will your volume be ten years from now?”

Is this something that anyone can know? The trouble is, the recipient of that questionnaire will give you their best guess and then all too often it is used as fact for forecasting and budgeting. If someone asked you that question about your own company or department, how confident are you that your answer will be true in ten years, and what level of financial commitment can be made today based on your answer? When asked this second way, most people tell me it’s a rough guess at best, with very low confidence.

If we can’t rely on asking each department for forecasts, then how can we plan a building that may last for decades before it is renovated?

- Don’t speak of the ocean to a well frog

Part of our job as architects, engineers, project managers and facilitators is to help clients make decisions, and we need to recognize that they are human and they don't know what they don’t know. For many people, being involved in the design of a new building is a once-in-a-lifetime experience. It is fine to ask people questions they know (or can know), such as history, current numbers of people, products, changes they would like to make, and even trends in their industry that the designers aren’t expected to know.

But when asking for a decision or input on trends in facility design or how they expect something to function in the future, we should recognize that people:

- Can only tell you what they know.

- Their experience may be more limited than yours.

- Many people don’t know the answer to your question but feel pressured to give you an answer.

A Chinese philosopher once said, “You cannot speak of the ocean to a well frog.” So if you need a decision from people who only know life in their “well” and they don’t understand the “ocean,” it would help for you to show them the ocean. This might include giving them virtual tours of similar projects, showing them the latest trends from other facilities around the country or around the world, and/or arranging in-person tours so they can experience first-hand what others are doing and learn what they would do differently next time. Only then they can start having an informed conversation about the ocean. I know many clients who said that such tours not only added tremendous value to the project, but it dramatically improved their ability to make informed decisions.

In part III of this series, I will discuss ten tools to achieve decisions that stick.

From the same author

Decisions that Stick in Pre Design and Construction - Part 1

Kurt Neubek is a Principal, Firmwide Healthcare Practice Leader, and Lean Advocate with Page, a 650-person architecture/engineering/interiors/planning/consulting firm with nine offices across the US and abroad. He has over 30 years of experience and has programmed and planned tens of millions of square feet of space across the globe. Kurt is an award-winning speaker, having presented at more than 90 national and regional conferences. He is a Fellow in both the American Institute of Architects and the Health Facility Institute, a Certified Facility Manager, LEED Accredited, Evidence-based Design Accredited and Certified, and a Six Sigma Black Belt. He is also an instructor for the Lean Construction Institute and the Construction Owners Association of America.