The most successful IPD teams can answer 3 questions:

- Why are we building?

- How are we building?

- What are we building?

Less successful teams eventually figure out what they are building and they may have spent some time determining how—but they never clearly understand why. After 10 years of structuring and watching IPD projects, we believe that “Why” is a critical first step and that IPD teams should work hard to understand the why and to communicate it continuously to all of the project participants.

By “Why” we mean the essential reason for undertaking a project. It is more than a program or a set of owner’s requirements. It is the problem or opportunity (or both) facing the project sponsor and reflects the value the project will bring and the values of the project team.

Understanding “why” is important to project success because:

- It aligns everyone to achieving the project goals;

- It establishes the criteria for decision making;

- It gives the participants purpose; and

- It provides standards for measuring project success (and sometimes compensation).

Alignment

A good film is when everyone involved is making the same film. A bad film is when everyone has a slightly different film in their head.

Sir Alan Parker

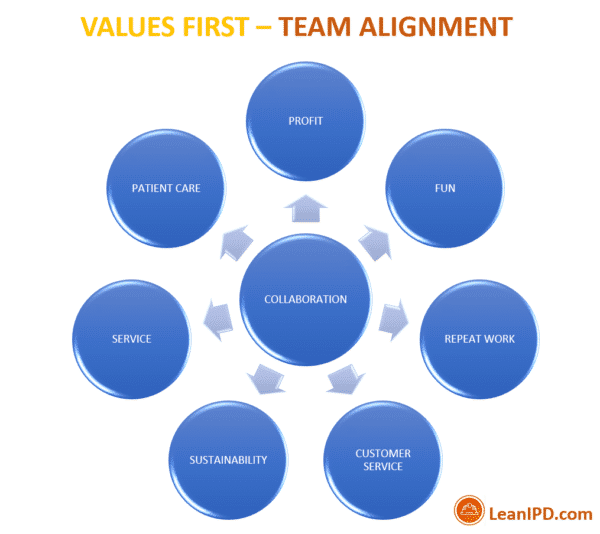

One of the most dysfunctional aspects of traditional project delivery is misalignment and local optimization. Because participants are siloed and compensated based on individual outcome, there is little hope of routinely achieving outcomes that are optimized to the project. Even on IPD projects we often find that at project inception, team members may only generally understand the project’s principal goals. Getting everyone on the same page is one of the principal benefits of a values workshop.

Understanding the project values is a first step in taking ownership of the entire project. Unless an effort is made to understand and commit to the project values, solutions will tend to remain locked into individual specialties.

Alignment also allows the parties to work independently and concurrently. Even in a co-located project, many decisions will be made during independent work. But if the end goal is known to all, it is more likely that the individual decisions will be consistent with the overall plan and will harmonize with other decisions. This leads to better optimization and less re-work. If the parties don’t have this common understanding, they are forced to work sequentially to avoid rework. The time loss in sequential work—as well as the loss to creativity—then becomes a major source of project waste.

Participants committed to the same values will design and build the same project.

Decision Making

When your values are clear to you, making decisions becomes easier.

Roy E. Disney

In a traditional project, the builders execute what they are told to build. Success is achieved if they build it for less than the bid/planned cost, and thus make a profit. “Why” is irrelevant because they only need to achieve “What” which is given to them. Whether the project is a success is irrelevant from their perspective.

In IPD, however, “What” is not a given, but it is developed during the project. And because the builder is an active member of the decision making team s/he must have criteria for choosing among the many alternatives that are possible answers to “What.”

Consider the choice of a chiller under an IPD or a design bid build project. In both cases, there is some flexibility because the contractor is allowed, in most DBB projects, to provide a chiller that is “or equal” to the specified unit or that meets a specification. Final choices are not made until submittals have been made and approved. Whether DBB or IPD, decisions must be made—but the process and the role of “Why” is very different.

In the public project, the contractor contacts vendors and identifies units that meet or exceed the specification. The contractor then compares them, probably with regard to delivery time, ease of installation and most importantly cost. These criteria that relevant to the contractor’s personal profit. Note that how well the chiller performs (as long as it met the specification) has no value in this analysis nor will design options be considered that have fewer or no chillers.

In the IPD project, the alternative chillers would be evaluated based on whether they had differences relevant to the project ‘s values. For example, if life cycle cost was a key value, the contractor’s criteria would be considered, but they would be balanced against the life cycle cost of the alternatives. Durability, maintainability and energy usage would become important factors. If sustainability was a key value, the team, including the contractor, might not only consider chiller alternatives, they might consider different building orientations, insulation, lighting strategies, windows or other factors that might result in reducing or eliminating the need for the chillers—or some of them. In the IPD case, the project values directly relate to the decisions to be made.

Thus, to make decisions in IPD, you need to know your values.

Purpose

A compelling team purpose is clear (which orients the team), it is challenging to achieve (which energizes the team), and it is consequential (which engages the full range of members’ talents).

Richard Hackman

Research on team motivation (and common sense) tells us that we like to feel that the work we do is valuable. Moreover, we are social animals that feel better when we identify with a group. Having a common purpose makes us members of the tribe and knowing that what we do is both useful and valuable gives us purpose. These factors lead to deeper engagement and more productive team members.

By defining and jointly agreeing on values we satisfy both purposes. By committing to the common goals, we identify with the group. We are all “insiders.” By having a positive purpose, such as building a school or hospital, we gain satisfaction by knowing our work is worthwhile. Even if the project is solely about creating a profit making venture, if we have an understanding of the full project, we have the satisfaction of whole and complete work.

Common values engage our hearts as well as our minds.

Standards for Success

What you measure is what you get. Period.

Dan Ariely

If what you measure is what you get, you best be very careful with what you measure. One of the reasons we get misalignment in traditional project delivery, is that our measurements—and our compensation systems—measure individual and not group outcome. The surprise is that we are surprised by the result.

If our values reflect what we really want to happen, shouldn’t we measure against our values? Even if we don’t directly tie the values to compensation (and that can be complex), if we track progress against values we will be much more likely to achieve them. Which takes us back to the beginning, because if we are going to measure against values, we really, really, need to know what they are.

Defining Values

When we run project or contract workshops we almost always include a segment on defining values. At a minimum, this is a several hour exercise that gets project participants working in small groups with other team members. We use the exercise as a learning moment for team dynamics and management, but the real purpose is to develop the project values. Interestingly, the workshop participants often remark that the value exercise was the most valuable (sorry about the pun) element of the workshop.

We have a methodology for running the workshop, which we believe works well, but the point is less how you define values than whether you do so. As long as you engage the right people in the process, avoid overpowering the quieter voices, and gain consensus on values, then you have made progress.

Once you have values, use them! Values can be used to develop specific goals. Specific goals can lead to developing tactics. And project management should regularly score the project against the goals. Do this and you will have a “star to steer your ship by.”

This post was originally published at hansonbridgett.com.

Howard Ashcraft has led in the development and use of Integrated Project Delivery in the United States, Canada and abroad. Over the past decade, his team has structured over 125 pure IPD projects and worked on many highly-integrated projects. He co-authored the AIACC’s Integrated Project Delivery: A Working Definition, the AIA’s IPD Guide and the text published by Wiley earlier this year, Integrating Project Delivery. A partner in the San Francisco law firm of Hanson Bridgett, he is an elected a Fellow of the American College of Construction Lawyers and an Honourary Fellow of the Canadian College of Construction Lawyers and is an Honorary Member of AIA California Council. In addition to his practice, he serves as an Adjunct Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Stanford University.