In Part I of this series Getting Decisions that Stick, we looked at the psychology of decisions and what information people need to make decisions. Part II describes ten techniques to help decision-makers make better-informed decisions, including the importance of identifying the decision-makers and making it clear to them which decisions will be needed by when. This final article of Part III focuses on actionable tools and tactics (#6-10 from the list below) that lean project teams can use to achieve better decisions.

Tools and tactics to make better-Informed decisions

- Explain to everyone which decisions are needed when

- Facilitate to foster informed decision-making

- Use high tech and high touch

- For data-informed decisions, make data actionable

- But don’t bet the farm on the data! Plan flexibility

- Facilitation techniques to make deciding easy

- Communicate cost and schedule impact early and often

- Recognize that most customers don’t understand floor plans

- A3s

- For really tough decisions, flip a coin

- Facilitation techniques to make deciding easy

In Part one we noted that one of the most valuable ways that project teams can influence getting decisions that stick is, “Don’t ask for decisions, facilitate them.” By “facilitate” I mean plan for and lead work-sessions and decision-making meetings in a way that will get to a durable decision. Becoming an excellent facilitator–like becoming good at anything–ideally comes from training, coaching, and experience. The following techniques are just the tip of the iceberg for being a good facilitator, but I believe most project teams can adopt them immediately on projects of all kinds.

Simple Decisions - Some of the decisions a project team needs are rather straightforward, such as when there are not many options available and there is a clear winner. Simple decisions don’t require much facilitation. The situation can normally be explained verbally along with the options and their costs and benefits, and a decision can be made. A visual (slide, flipchart, graphic in a document) may not be required, but having one will help people focus on and understand the decision they are being asked to make.

Rubber Stamp Decisions - For many decisions, particularly those with a finite list of possible options, and especially if the decision-makers are likely to rely on the recommendation of specialized professionals, a simple tabular comparison may be an adequate visual to use when explaining the decision to be made. For example, if the structural engineer and the geotechnical engineer say that, based on the soil conditions, there is really only one feasible foundation system, then the decision-makers usually accept the recommendation as presented. (Unless there is another structural engineer on the decision committee; that may lead to a livelier discussion prior to approval!) But project teams should still facilitate the decision by providing a visual with at least the recommendation and what the alternatives are, noting the quantitative and qualitative reasons that support the recommendation. Decision-makers want to be assured that the recommender “you did their homework” and evaluated alternatives.

Remaining Decisions - Almost all decisions needed during design, and some during construction, are not so straightforward. They benefit from more guided facilitation techniques. Many of the decisions that are needed for a project have a nearly unlimited number of solutions, particularly during the design phases. If decision-makers are asked to make a decision but they feel the options presented are too limited or the options do not adequately address their criteria, they may send the team “back to the drawing board” multiple times. Such decisions require much more preparation and guided facilitation to help shorten these cycles and more quickly get to a durable decision. Valuable facilitation techniques include:

- First, understand the decision-makers’ criteria. Even if the owner has provided their stated criteria for a decision, and even if the project team has gathered additional criteria, recognize that sometimes decision-makers are not aware that they have unstated criteria until they are faced with a particular decision. Therefore, if a team is struggling to gain consensus on a solution, back up and first help the decision-makers gain consensus on the criteria they will use to make the decision.

- Clearly separate the nature and timing of decisions. I sometimes see teams struggle to gain consensus or a decision because the topic or question has been posed too broadly, effectively asking multiple questions at once. This can almost always be solved by building consensus and gaining decisions in sequence: first on the planned operations, then programmatic decisions, and then decisions about design and construction.

- Operational - Focus first on helping the owner and users think through and document how they plan to operate the facility. This is sometimes called the functional program or the concept of operations. Focus on documenting what they want to do in the building, how they want to do it, the desired customer experience, etc. Often users will say, “That depends on the building layout.” It is the facilitator’s role to explain that the team will design around the ideal operations. Then help them think through the ideal flow and range of uses. For teams trained in Lean, using a Value Stream Map may be useful.

- Programmatic - Building directly from the desired operational model, the team can then develop the facility program that should include further exploration of quantitative and qualitative goals, desired flows, adjacencies, and other programmatic concepts. All of these ideas should then be quantified into the number of rooms, the sizes of those rooms, other technical criteria, and the anticipated schedule and budget to achieve the program. To be most successful, include research into similar projects. If Target Value Delivery is being used, it should start during the programming phase.

I don’t think enough people in design and construction realize how many decisions about a building can, and should, be made prior to drawing any floor plans or elevations. Based on the operational concepts, programmatic concepts, site analysis, relevant codes and regulations, and research into similar facilities, the programming team should have a very clear idea of the scale and nature of the facility. Documenting and gaining approval of the operational and programmatic aspects is extremely helpful to the design and construction team and the decision-makers because it narrows the field of options explored during design, leading to decisions more quickly.

- Bring research, context, and comparables - Whenever someone is asked to make a decision, we all have unstated criteria along the lines of, “What is normal, or expected, or industry standard? How does this compare to our own standards, and what are our peers and competitors doing? How do I know if my decision, or the options being presented, are reasonable? Will I find out later that it was a bad decision or will I look bad for having made this decision?” With these concerns in mind, facilitators who anticipate and provide the answers to these unstated questions can significantly improve decision-makers’ confidence that they are making an informed decision.

- Optimize the whole - Nearly every decision we make has unintended consequences. By optimizing one area, teams often don’t realize the consequences to other areas. For example, an individual or a cluster team may choose to save money in the building skin by reducing the insulation to code minimum. But this may increase the size and cost of the HVAC system beyond the savings in insulation. To help people understand the broader impacts of each decision, design teams need to intentionally make visible what the ramifications are. For example:

- During programming, spreadsheets can be formatted to show the bottom-line consequence of programmatic decisions on area and cost. So if someone asks to make a room type just 5 square feet larger, they undoubtedly don’t know how many of those rooms are impacted, how much the circulation and building support areas also have to increase, nor the impact on 30 years of operating expenses. But if the facilitator is prepared to show those implications live, during the meeting, people can make much better-informed decisions.

- Many other decisions can also benefit from using already-prepared computerized templates or models during a meeting for “what if” option analysis. For example, it may be beneficial to have a person in the meeting who can run real-time options in the building’s energy model. Other forms of simulation modeling may also be beneficial, but the complexity of running new simulations may take too long to run in real-time during a meeting.

- Live 3D modeling can also be extremely beneficial. When the project team presents a design option or recommendation, often the decision-makers or reviewers will ask “what if” questions, wondering if a variation they have in mind would be an improvement. Design teams who can make those changes in real time during the meeting so everyone can see the change in 3D are better able to build consensus and get a decision sooner, which may cut weeks from the project schedule.

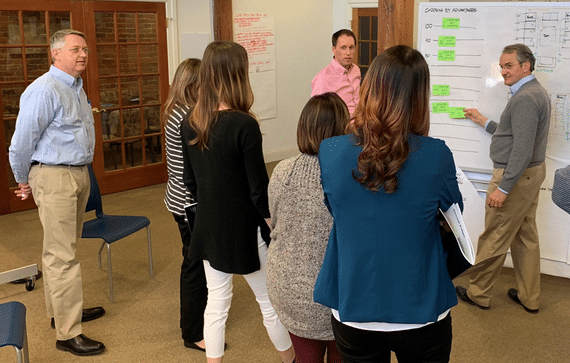

Choosing By Advantages (CBA) is a decision-making system that is used by many members of the Lean Construction Institute. It is an organized system to evaluate alternatives based on factors, criteria, and the importance of advantages. Facilitators interested in using it should seek training and coaching from skilled practitioners.

Image: Kurt Neubek

- Communicate cost and schedule impact early and often

Finding out after a decision has been made that there were unstated cost and schedule impacts is one of the surest ways to unravel a previous decision. While this point is mentioned in other sections of this article, it is worth a dedicated paragraph because it also stands alone for its “bang for the buck.” Project teams who want to improve the durability of their decisions can start by identifying cost and schedule impacts for each option being considered. Having a cost estimator on the project from the beginning is one of the key benefits of having an integrated project delivery (IPD) team.

As noted throughout this series, decision-makers do not rely solely on cost and schedule. Other quantitative and qualitative criteria are also important. But primary functions, cost and schedule are usually the first set of criteria used by decision-makers.

- Recognize that most customers don’t understand floor plans

For a layperson, 2D drawings are simply not the most effective way to communicate a 3D design or 4D (including motion) proposal. For most people, two-dimensional drawings and diagrams work well for discussing 2D topics such as adjacencies and measuring travel distances between rooms. And 2D drawings may be adequate for other decisions that are largely 2D, such as interior and exterior elevations. But buildings are three dimensional and often spatially complex, so having full-size 3D options to evaluate is much more effective at helping people understand the options and make well-informed decisions, reducing surprises and changes later. Full-size 3D options are especially valuable for people who are kinesthetic learners but are equally effective for all learners.

Being able to fully experience a thing before you make a decision to buy it seems to be a basic human trait. Before you buy a car, you may start by gathering relevant data and reading others’ opinions and recommendations that will lead you to a short list of options that meet your criteria. But to actually make the final decision yourself, don’t you want to sit in several cars and test drive them to experience them in 3D and understand all of their nuances? When project teams ask decision-makers for a decision, we should respect that to make a 3D decision, it helps to present the options in 3D, as close as possible to the finished solution.

Image: Kurt Neubek

Except for model homes or similar facilities that will be duplicated many times, most projects cannot afford the time, money, and space to build a complete full-sized 3D model of the entire project with every color and material. But for key decisions, providing at least a limited number of mock-ups of critical areas can be very helpful for decision-makers. After making initial decisions using small-scale 2D drawings, many design teams and owners rely on mock-ups to confirm critical decisions, including:

-

- Renderings are admittedly 2D representations of 3D space. Whether created as quick sketches by a person skilled at drawing in perspective or through a 3D computer model or a video fly-through, perspective views are undoubtedly the most common way to communicate 3D space before it is built. After all, the project team is already “building” the project in 3D in the computer before it is built physically, so there are obvious benefits to using the computer model to communicate proposed design options. While renderings are beneficial, they are not immersive enough for people to evaluate detailed options where clearances and workflow are essential.

- Virtual Reality also uses the computer model, but it allows the viewers to feel more fully immersed in the space at full scale prior to construction. Some people love using VR; others feel motion sick. One decision-maker I know who was using VR for the first time on a project found it extremely informative. After reviewing the area in question, she stated, “Now I want to review all the other areas where we made decisions over the past weeks because now I can better understand the whole building in 3D.”

- Material mock-ups have been used for generations on construction sites to allow decision-makers to see the selected materials full-size as they will be installed in order to make final approvals.

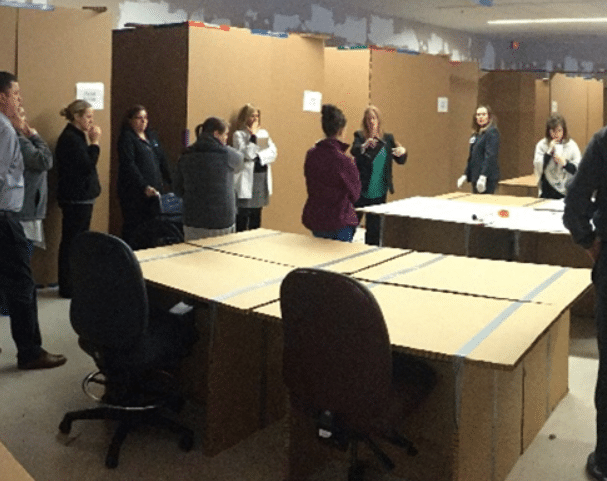

Cardboard City is a term sometimes used when project teams build out a simplified version of an entire suite or department full size, generally in a warehouse or vacant space. The walls are simulated using cardboard or foam core panels, allowing people to understand travel distances, test workflows, check clearances for moving large pieces of furniture or equipment, and evaluate potential revisions quickly. This is usually done late in schematic design to confirm the already agreed-to floor plan arrangement.

Image: Kurt Neubek

- Full-size 3D mock-ups of key rooms are used to evaluate more details and clearances within rooms. Because of the cost, they are usually reserved for key rooms. In early design phases, these are intentionally made of materials that encourage revisions and experimentation; later in design, they may be fully constructed rooms for final approval.

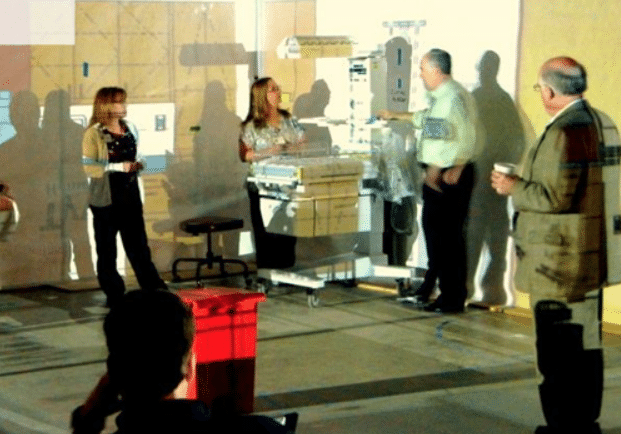

- Clinical Simulation in a mock-up room is an approach I call a “4D mock-up.” When processes happen in a space over time (the fourth dimension), just looking at a 3D mock-up with one scenario in mind does not adequately recognize the importance of the activities that are planned or are foreseeable in a space. Anywhere processes happen, it is helpful to walk through, or simulate, the range of processes in the mock-up. The team will likely identify a situation or scenario they had not previously discussed that the room needs to accommodate.

Hybrid Virtual 3D - I have not seen this widely used, but I found it to be very effective. The owner scheduled a large empty room with two long walls and the design team projected the key room designs from the Revit model onto the walls at full scale. They then wheeled in furniture and equipment, and any revisions to the walls or wall-mounted items were revised immediately in the computer model. The team then cycled through a series of rooms in this same fashion.

Image: Kurt Neubek

Finally, the best way to communicate a 3D solution is often not with mock-ups at all, but instead by visiting and evaluating existing facilities. It is rarely beneficial to start with a blank paper and intentionally reinvent the wheel, particularly for a standard room type that exists in many similar facilities. If the project team can find existing rooms that are very similar to what is being proposed, then much can be learned by interviewing the people who use the facility, conducting a form of Post Occupancy Evaluation, and identifying ways that room can be improved.

- A3s

Readers who have been exposed to Lean in Design and Construction may be familiar with A3s. An A3 is a one-page format (A3 paper size throughout most of the world; 11x17 in North America) used to communicate a situation concisely. It also serves as a record of how key decisions were made and why. Design and construction teams may use A3s for a variety of situations (e.g., proposals, status reports, problem-solving), but fundamentally an A3 is intended to encourage the use of a rigorous scientific method and to communicate those findings concisely. I have seen too many people who have not been trained in creating A3s present a slide showing options A, B and C and describe it as an A3. Applying the principles described in this series can help you create A3s that will more likely lead to a durable decision.

The core elements of an A3 should include:

- The left side summarizes the current state:

- What is the question to be answered or the problem to be solved?

- Background and context of the situation, perhaps including industry standards and relevant best practices that highlight the problem.

- Current condition, including relevant metrics, often with graphs and charts

- What is the goal or desired target condition? Clearly identify the gap.

- What is the root cause of the gap? This requires analysis and consensus-building. The root cause is rarely what appears obvious; those are likely symptoms created by other causes.

- The right side summarizes proposed actions/countermeasures/recommendations:

- Based on a thorough understanding of the root cause of the problem, what are some potential options or countermeasures to be considered? These are often presented as a tabular comparison of options. This is also a good place to apply Choosing By Advantages if that method is being used.

- Implementation - For the proposed direction, what are the specific next steps and actions needed? Is a test or pilot study needed to confirm the proposal will solve the problem? This section may need to be produced after review and agreement on the proposed option or countermeasure selected.

- Follow-up - Depending on the context of the question or problem, there may be a scheduled or periodic follow-up of the situation to check whether the option or countermeasure selected actually solved the problem or if more work is needed.

When preparing an A3, particularly the section evaluating potential options, be sure to factor in all of the Getting Decisions That Stick lessons from this series, including:

- How well does each option meet the core functional requirement?

- What are the costs? Not just initial cost, but also long term life cycle costs?

- How does each option impact schedule?

- How does each option compare against other known project goals such as sustainability, energy conservation, long term flexibility, maintainability, being a good neighbor, etc.?

- What are the unstated or less tangible criteria such as perceived quality or the “optics” or potential political implications?

- Will a simple tabular comparison suffice, or will decision-makers need other ways to understand, compare, and make an informed decision? Diagrams, renderings, photographs, and construction details are usually beneficial. Other decisions may require a site visit or review of product samples. Another tenet of Lean is to not make a decision in a conference room; instead, “go to Gemba,” the place where the work is done or the value is created, and talk to the people doing the work. This is often applicable to programming, design, and construction decisions.

- For really tough decisions, flip a coin

Lastly, for really difficult decisions, even after using all of the above techniques, a decision-maker may still be unable to make a decision. This can be especially true for complex decisions where the outcome and ramifications of the decision are nearly impossible to know and the perceived risks are high, such as whether one should accept a job in a different city. In these cases, a proven technique is to just flip a coin, saying, “Heads I move, tails I stay.” Then observe your own reaction to the “decision” made by the coin. If, at the moment of the reveal, you silently said, “Yes!” or conversely, you felt your chest tighten, then you have your answer. It's a technique to help reveal a decision your heart may already grok, but your brain may not yet have rationalized.

There are people who say that all decisions are based on emotion and justified with facts. This may be true. There are certainly some people who make decisions this way, and there may be specific types of decisions that we all make this way. For example, judging whether to hire a person. If we instinctively like the person and feel they would be a good fit, we may not be able to express why, so we “sell” them to others by highlighting the accomplishments on their resume (justifying with facts). Similarly, artists and designers may create a design that they can feel is a good solution, but they may not have created it through a logic-driven sequential process. Many designers have learned the value of “post-rationalizing” a design by creating very rational reasons to explain the design to others–even if those were not the reasons used in creating the design. Intuition and gut feeling are powerful factors that shape the way many people make decisions, so respecting that process can often help teams get to durable decisions.

If you have had experience with these or other techniques to get decisions that stick, please share your thoughts with me at kneubek@pagethink.com.

From the same author

Decisions that Stick in Pre Design and Construction - Part 1

Ten techniques to foster informed decision-making in Pre Design and Construction

A Project Team's Role in Getting Durable Decisions

Feature image: Tim Gouw via Unsplash

Kurt Neubek is a Principal, Firmwide Healthcare Practice Leader, and Lean Advocate with Page, a 650-person architecture/engineering/interiors/planning/consulting firm with nine offices across the US and abroad. He has over 30 years of experience and has programmed and planned tens of millions of square feet of space across the globe. Kurt is an award-winning speaker, having presented at more than 90 national and regional conferences. He is a Fellow in both the American Institute of Architects and the Health Facility Institute, a Certified Facility Manager, LEED Accredited, Evidence-based Design Accredited and Certified, and a Six Sigma Black Belt. He is also an instructor for the Lean Construction Institute and the Construction Owners Association of America.